Here it is, ladies and gentlemen. The very list nobody asked for but I’m giving everyone, anyways.

Self-deprecation aside, here is my list of my ten favorite movies from the year. Not what I think is the best, mind you, just what I loved the most. As I’ve said many times before, there is no conversation in stating, “These are the best movies of the year!” It’s an opinion posed as fact. Instead, this is just what mattered to me the most this year. In approaching it that way, it allows me to fudge where I put certain movies. While I think some films are impeccably made, like Locke or The Railway Man, I will always enjoy superheroes and crazy science fiction a little more. Basically, it allows me to be honest not just with myself, but with all of you, as well.

But enough rambling. I always enjoy putting these lists together, so I hope you enjoy them as well. And as always, let me know what you think. If you agree, disagree, or are kind of indifferent, feel free to leave a comment or share or anything you like. Anything and everything is more than appreciated.

10) Blue Ruin

This haunting little tale of revenge is one I am not likely to forget anytime soon. It’s a film that flourishes in silence, a film that wants you to feel every knick and every bruise. From the opening moments, Blue Ruin is a slow motion car wreck, and writer/director Jeremy Saulnier handles it beautifully, allowing the images to speak far louder than words. I’ve only seen Blue Ruin the one time, but I feel like that one time was more than enough.

9) Dawn of the Planet of the Apes

It kind of amazes me that Dawn of the Planet of the Apes exists. Not because we have a big budget Hollywood action movie in which apes ride horses whilst toting machine guns (which, as I’m sure you are well aware, delights me that I can even type), but because of the thematic material the film plays with. Dawn is a brilliant allegory for race relations with Caesar playing the pacifist Martin Luther King Jr. role and his right hand ape, Koba, playing the Malcolm X role. They are two sides of the same coin, approaching the same goal from two different directions, and the film smartly lets it play as morally ambiguous. It may take sides in the end, but it never paints any side – including the humans, who are essentially the villains of the piece – as being inherently wrong. It’s a smart approach and it allows the film to not only be entertaining, but also feel entirely relevant.

8) Captain America: The Winter Soldier

Winter Soldier is, to me, Marvel’s biggest accomplishment as a movie studio. The film acts as a great superhero movie with big action and crazy spectacle, but it is also amazingly compelling as an espionage conspiracy thriller. It’s the first Marvel film to strike a pitch perfect balance between superheroes and genre and directors Anthony and Joe Russo rise to the occasion. They get why Captain America works, that he is a man lost in time, and they allow that to be his emotional core without sacrificing Cap as a badass. It’s fantastic and I feel confident saying that The Winter Soldier is easily Marvel’s best film to date.

7) The Raid 2

Words cannot express just how cool this movie is. Coming hot off the heels of The Raid, one of the best action movies of the last decade, writer/director Gareth Evans took what made the first film so amazing and turned it up to 11. Not only is the action so bone-breaking and face-crunching as to be unlike anything I’ve ever seen, but Evans manages to maintain a stylistic approach as to highlight the craft. The choreography and the stunt people always take precedence, which means Evans uses many static cameras and wide shots, really allowing the audience to marvel at the insanity they are watching. But The Raid 2 is more than just action. There is a big story at play here about gangsters, backstabbing, and corruption and Evans marries the two in such a way that they naturally fit. It’s impressive filmmaking and it makes me beyond excited to see what Evans has in store for the inevitable The Raid 3.

6) Noah

Audacious. It takes some real confidence to make this kind of film and try to sell it to a mainstream audience because what director Darren Aronofsky has done with Noah is completely obliterate any notion people may have had about the story of Noah’s Ark. This gets incredibly dark, examining what it really means to flood the entire earth in order to cleanse mankind, and Aronofsky never flinches. That is ballsy enough on its own, but by adding the Watchers, giant, stone covered angels who have fallen to earth (creatures that are a large part of the Jewish Noah myth), and by including one sequence that beautifully marries evolution and Creationism in a swift three minutes, Aronofsky seems to be out to please nobody but himself and I absolutely love it.

5) Jodorowsky’s Dune

Some of the most interesting questions to ponder are what ifs. What if I did this instead of that? What if I ended up with that person instead of this one? They are ultimately pointless questions as the past is the past and what happened already happened, but they are fun to think about and Jodorowsky’s Dune is a great examination of a single question: what would have happened if director Alejandro Jodorowsky would have made his version of Dune? Now, I am 100% willing to admit that this is a very niche film. Not a lot of people are aware of Dune, let alone Jodorowsky, one of the weirdest filmmakers who has made some of the most surreal films I have ever seen, but it’s a fascinating story of lost potential. Had Jodorowsky made his film, our modern media landscape would probably look very different from how it does now. Or, at the very least, we would have one more incredibly strange film added to the history books.

4) Snowpiercer

By far one of the stranger concepts to come out in theatres this year, Snowpiercer is unsubtle science fiction of the highest order. It is incredibly on the nose, but director Bong Joon-Ho has crafted one of the best, most relevant science fiction tales in years. Essentially telling the story of the 99% versus the 1%, the film is funny, violent, and occasionally surreal, but always in service of a larger message. It’s dark, but it’s also tinged with hope, and it all adds up to make one of the most enjoyable, most surprising sci-fi movies of the year.

3) Guardians of the Galaxy

I can’t say I had as wide a grin on my face during any other film this year than when Drax the Destroyer laughs maniacally while mowing down tons of evil henchmen with a spacecraft. I know I already included one Marvel movie, but I just couldn’t not include this. While Winter Soldier may be Marvel’s best movie to date, Guardians of the Galaxy is easily their most enjoyable and a lot of that is due to director James Gunn’s involvement. He brings a lightness to the world and this lovable band of misfits without cutting down on the more explode-y bits, and he manages to inject the film with so much heart that the film quickly became my favorite Marvel movie yet made. This is a film that wisely stands apart from everything else Marvel has released and that is partly what makes it so special. From the characters, to the world, to the operatic nature of the story, this is big sci-fi fantasy and I can’t wait to see more of it.

2) Her

While a lot of critics included this film in Best Of lists from last year, the film technically didn’t get a wide release until January (aka, I couldn’t see it until January), so I’m including it now. And with good reason. Her is the most personal film of Spike Jonze’s career. It’s real and it’s sad and it’s delightful and it’s painful and it’s beautiful. In other words, it perfectly captures the entirety of a relationship from beginning to end, from the first initial rush to the crushing pain as it falls apart. The details are so precise and nuanced and mature as to be immediately universal, but what makes it so amazing is the way Jonze folds it all into a brilliant science fiction tale about artificial intelligence. Her isn’t the easiest sit. I would find it difficult to just turn it on on a whim, but that’s because it’s so painfully real that it takes a toll. The film may be about a man falling in love with his operating system, but it is one of most honest depictions of love I’ve ever seen.

1) Nightcrawler

It was a no-brainer to put this in the top spot. Nightcrawler is a film that has eaten at me since I saw it. It’s dark, it’s gross, it’s gleefully unapologetic, and it ruthlessly rubs the audience’s face in our current media landscape. It’s an angry film, a contemporary approximation of Network, and considering this is writer Dan Gilroy’s first time taking both writing as well as directing duties, that is no faint praise. And I would be remiss if I didn’t bring up Jake Gyllenhaal as the main character, Louis Bloom. Gyllenhaal has utterly transformed himself in the role. He plays Bloom with a calm, self-assured attitude while simultaneously looking like he’s always on the verge of stabbing somebody in the street, and the effect is amazingly unsettling. The audience never quite knows what to think about Bloom. Is he insane? Or is he just incredibly driven, willing to do anything to obtain his dream? But maybe that’s the point. Are pervasiveness and insanity mutually exclusive or are they one and the same, one the next evolutionary step from the other? It’s a big, heavy question to ask and it’s smart to not answer it. Instead, Gilroy leaves the audience to draw their own conclusion, and that may be the most terrifying thing of all.

So we’re nearing the end of December, which means the year is just about over, which means everyone is starting to publish Best Of lists in every category. I’m currently working through my own Top 10 Movies of 2014 list, but before I get to finishing and posting that, I wanted to do a list of movies not necessarily from 2014, but that I simply watched throughout the year and greatly enjoyed. I did the same thing a few years ago and while I’m not sure many people are really interested in seeing what new and old movies I watched throughout the year, it helps me put the year in a bit more perspective. For example, I keep a running log of what I call “New to Me” movies (movies I watch over the course of the year that I had never seen before) and after sifting through this year’s list, I realized I did not watch nearly as many movies as I typically do in a given year. This may be because I put more of my time into catching up on TV shows and rewatching favorite movies of mine more than I probably should have, or it could be because I just needed a sort of breather, a chance for me to figure out what I’m really doing. Chances are the answer lies somewhere in the hazy middle ground, but that’s going into something else entirely. My point is that this list is as much a way for me to reflect on the past year as it is a way for me to recommend new and old movies to the small handful of you who read this.

Either way, since I did not watch as many catalogue titles this year as I usually do, this list also acts as a sort of Runners Up list to my Favorite Movies of 2014. Nothing here is in any particular order, but that is as it should be. This isn’t a way for me to rank. It’s simply a way for me to celebrate films of past and present and to share what mattered to me the most this year.

As always, feel free to comment or share or what have you. And thanks for reading!

The Act of Killing (2012)

Every now and then a film comes out that is not only relevant to our culture and the world around us, but is also downright important. The Act of Killing is one of those films. It is by no means easy to watch and I struggle in recommending it to people, if only because it is so gruesome and tells a true story born entirely of pain, torture, and death, but it is a documentary I feel everyone should see at least once. By telling the story of the Indonesian killings of 1965-66 through the mouths of the very people who committed the mass atrocities, the filmmakers not only gain a unique perspective, but it simultaneously allows them to tell a parallel story of the fragility of the human mind and the walls and barriers we create in our own subconscious to get through the day to day. It’s amazing, horrific, and breathtaking and a story I’m not likely to ever forget.

Stories We Tell (2012)

On a similar note, Stories We Tell is a beautiful documentary about the ways we bend reality and our pasts to make life seem a little more palatable, a bit easier to digest. It’s more personal than anything I expected, with writer/director Sarah Polley not only telling her family’s story, but laying bare family secrets few people would want made public, and the film stands out because of it. This isn’t just a story, it’s reality, and Polley plays with that idea in such a clever, mind bending way that what once seemed clear is shattered in the film’s closing moments. This is finding order in chaos, art in destruction, and it brings to mind all kinds of questions about what history and memory really are. Once a moment is passed, it’s gone forever. After that, it’s simply a story we tell ourselves.

The Lego Movie (2014)

“And now for something completely different,” you may be saying. Yes and no. While The Lego Movie is fun and silly and amazingly clever and self-aware, what really blows me away is just how deep it gets. Directors Phil Lord and Chris Miller somehow got away with decrying lack of creativity and playfulness in a film ostensibly about Legos by telling a story about self-identification and the possibilities that are inherent in anyone and everyone. It’s lovely and smart and a refreshing step away from the standard story of the Chosen One and destiny. Emmet isn’t a hero until he makes himself a hero. What could be better?

Chasing Ice (2012)

And now for something completely terrifying. Chasing Ice is a warning sign of the highest order, a giant red flag in the nonsensical debate about whether or not climate change is actually a thing. Filled with stunning footage and photography, this documentary examines the ever-receding ice shelves in Alaska, Iceland, and Greenland. The film smartly shies away from the causes, instead simply providing hard evidence as to what is happening in the uppermost corners of the globe. It’s shocking and terrifying, and running at a brisk 75 minutes, the film quickly makes its point and gets out, leaving little to question. If you want to know what it really means when scientists state that the ice is melting, watch this film.

Vernon, Florida (1981)

I love documentaries with a point of view and a real story to tell. They are important and engrossing and they can highlight aspects of human nature that we may not enjoy looking at. And then there are documentaries like Vernon, Florida, a film about a town and its people and not much else. I’ve seen a few documentaries now by director Errol Morris and he has an amazing way of presenting a people without any sense of judgment. He’s not making a statement or making fun of them, he is simply showing them as they are. As a result, Vernon, Florida is weird and hilarious and entirely genuine. There is never a sense that Morris is editing the film to make these people look bad. This is just who they are, which means they are eccentric and maybe a little bit out there. It’s an amazing portrait of a small town and its local color and with a runtime under an hour, I couldn’t help but love every second of this.

The Red Shoes (1948)

Classic cinema can sometimes be like homework. It may hold a significant place in history and it may be crafted well, but it doesn’t always mean the film is the most entertaining sit. The Red Shoes is not such an example. It is a film whose artistic merit does not hinder its entertainment value, a film that is easy to marvel at and deeply appreciate while adoring it as a great story well told. From its use of Technicolor to the music to the choreography to the writing, it is easy to see why this story of love, passion, and obsession in the world of ballet is largely regarded as being one of the best films ever made.

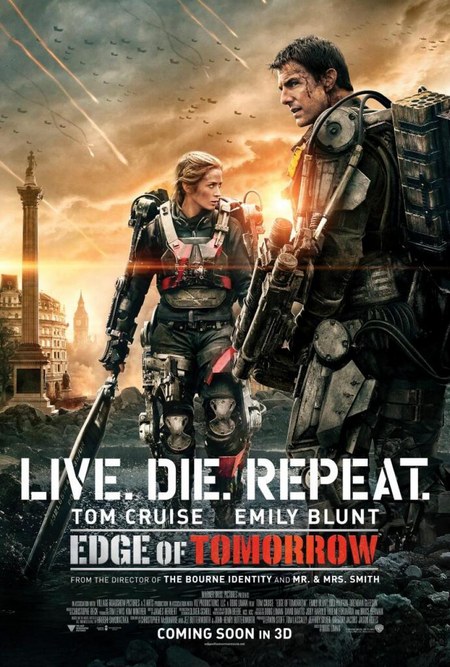

Edge of Tomorrow (2014)

Edge of Tomorrow is one of the best sci-fi films of the year that almost no one saw and I don’t understand why. It’s smart, it’s fun, and it incorporates some really cool time travel mechanics to tell a strong story set during a future war against an invading alien race. I have a feeling part of it was due to Tom Cruise’s involvement, but for my money, Cruise is perfect in his role here. He’s charming, funny, and maybe a little arrogant, but that’s the point. What’s great about his performance here is that he gradually becomes a hero rather than starts as one and it makes his casting particularly inspired. While Cruise is typically the untouchable hero, he dies a lot in this film; maybe a good 20 times. If you don’t like the man, this is the movie to see. But what really bums me out is that the film features one of the best female roles in years played by Emily Blunt and hardly anybody knows about it. Where Katniss Everdeen is more a symbol than anything, Blunt’s Rita Vrataski is a straight up badass. Not a badass woman, mind you, just a badass, and it’s amazing to see this kind of forward thinking portrayal in a big budget Hollywood action film. So, please, don’t let this one fade into oblivion. I’m so happy it was made, but it deserves far more than it got. This is why we can’t have nice things.

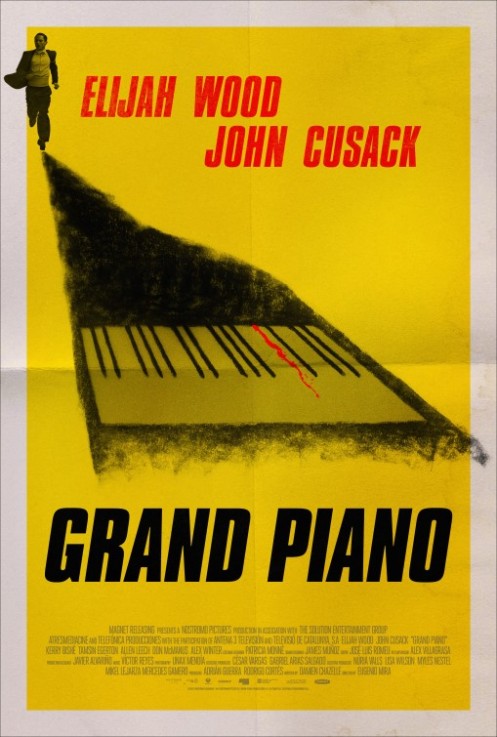

Grand Piano (2013)

There’s nothing like some good old-fashioned pulp to clear the palette. Grand Piano isn’t high art, nor is it trying to be. What it is is a tense thriller wherein a pianist must play an “unplayable” piece of music perfectly or a sniper will shoot him in the head. Yeah. It’s delightfully ridiculous and it feels to me like the type of film Brian de Palma would have made in the 70s. It’s stylish, violent, and a little over the top, and Elijah Wood and John Cusack seem to be having a great time. And really, it’s hard not to. It’s fun and sometimes that’s the hardest trick to pull off.

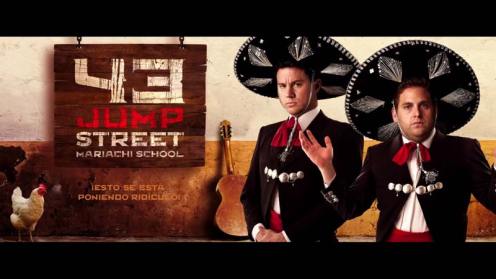

22 Jump Street (2014)

What’s that? Two movies by Phil Lord and Chris Miller in a single year? And both of them are great? I shouldn’t be surprised. And, really, I’m not. These two young directors have proven time and again that they can take junk and turn it into gold. The Lego Movie could have so easily been garbage, but it ended up being heartfelt, sincere, and one of the best family films of the year. 22 Jump Street, too, should have been terrible. It was intended as a cash grab, plain and simple. Release more of the same and everyone will be happy. But instead, Lord and Miller managed to twist the film into one of the weirdest, best comedy sequels I’ve ever seen. The way they call bullshit on standard sequel tropes is clever and knowing and the way they have Schmidt and Jenko’s relationship basically play out as a love story this time out is a brilliant spit in the face to how Hollywood sequels normally function. This is big budget punk rock filmmaking at its finest. Yes, the film is undoubtedly more of the same, but in the best, most hilarious way possible.

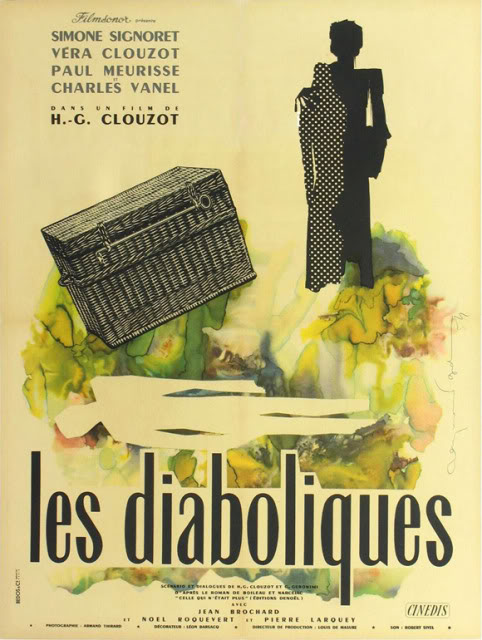

Diabolique (1955)

This is easily one of the best ghost stories I have ever seen, which is remarkable if you know the film’s ending. It is a tense thriller about murder, vengeance, and the stresses they can put on the human psyche, but it is also undeniably a ghost story, and a scary one at that. The film’s deliberate pacing and constant questioning of what is and is not real bring to mind Edgar Allen Poe’s “A Telltale Heart” and it all culminates in one of the most subtly horrifying images I’ve seen all year.

Ernest & Celestine (2012)

If you really must know how much of a softie I am, just know that this film melted my heart in a matter of seconds. It’s flat out adorable and is the exact type of animated film I love coming across. It’s sweet, it’s beautifully animated, and it is ten different kinds of cute, but it never feels overly precious. The film occasionally shows some teeth, allowing the stakes to feel real, and it balances the film out nicely. Story wise, it isn’t anything particularly new, but when the outcome is this good and sweet, it’s hard not to recommend.

Cuban Fury (2014)

This film, for me, is a particularly strong example of how a cast can elevate any given material. Cuban Fury is very by the numbers. Nothing about the film is particularly new or exciting and I could tell within the first 10-15 minutes how everything would play out. And, sure enough, I was 100% correct. But because the film stars Nick Frost, Rashida Jones, Chris O’Dowd, and Ian McShane, all of whom dance their heart out to salsa music, suddenly everything clicks and pops. Frost and O’Dowd bounce off of each other like pros, Jones is as adorable in her slight awkwardness as ever, and McShane is delightfully crusty as a dance instructor. They take what should be as vanilla as you could get and make it fun and enjoyable. Is it great? No. But it’s vibrant and energetic and it only reinforces my love for Nick Frost. And yes, the man can dance.

The Sacrament (2013)

Of all of the indie horror directors working right now, Ti West is easily my favorite. With House of the Devil and The Innkeepers, West proved that he could create hair-raising tension and a great sense of atmosphere in standard horror settings; i.e., big, scary buildings in stories about ghosts and the occult. The Sacrament marks a nice shift in approach for West. Instead of focusing on traditionally scary subject matter, his focus is on the real, psychological horror of cults and it is downright terrifying. Largely influenced by the Jonestown Massacre of 1978, The Sacrament is not about monsters or ghouls, but about the fear of being surrounded by a hive mind of religious zealots who have been brainwashed. Its use of found-footage is smart and inspired and it makes the film feel very real and immediate. The scariest thing can sometimes be ourselves and West captures that idea perfectly.

The Final Member (2012)

The Final Member is one of the oddest documentaries I’ve seen in years. Following a man who owns a penis museum in Iceland, the film is about his search for someone to donate the first human specimen. If that sounds trashy to you, I understand, but you are grossly mistaken. What sounds weird and gross actually ends up being a surprisingly human examination of what we pass down through the generations, of the legacies we leave behind, and, yes, how some people measure masculinity. There is definitely humor to be found here, but that doesn’t mean the filmmakers are out to pass judgment; they simply examine and document. It’s very evenly keeled and when dealing with subject matter like this, that’s no small feat.

Gone Girl (2014)

David Fincher has long been established as a very dark, grounded, pessimistic director. His films tend to be ugly and unafraid to get dirty, often times displaying humanity in an unflattering light, so when it was announced that he would adapt Gillian Flynn’s best-selling novel to the big screen, a lot of people assumed it would amount to watered down Fincher. After all, he had never done anything entirely mainstream, so how would that even look? It turns out it’s still pretty damn grimy. Gone Girl is how I imagine Fincher views the world and the way people consume media. It’s grossly unfettered and the way Fincher refuses to pull punches is not only admirable, it’s downright astounding. He takes the material into darker territory than I think most fans of the novel would imagine and he leaves the audience with a decidedly bitter taste in their mouths. This is impressive work and if it is an indicator of how Fincher works in the mainstream, I don’t think we have anything to worry about.

O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000)

I recently went on a mini-marathon of all of the Coen brothers films I hadn’t yet seen and of all of them, I have to admit that O Brother, Where Art Thou? was one of my least anticipated. I remember seeing pieces on TV when I was younger and it just seemed weird and kind of boring. Of course, it didn’t help that I wanted nothing to do with country and folk music when I was at that age, so nothing about the film appealed to me. But I’ve grown since then, my horizons broadened, and by the time the film was through, I was blown away. This is the Coens at some of their most playfully avant-garde. Telling Homer’s The Odyssey in the context of a runaway chain gang during the Great Depression may sound artsy-fartsy, but the Coens instill the film with their trademark humor and wit, allowing the film to feel like classic literature without it being musty. It’s a wonderful balancing act and the film ends up being probably one of the best from the two brothers.

Obvious Child (2014)

Abortion is a tough subject to handle in movies, let alone comedies, let alone romantic-comedies. It’s touchy, but it’s also so common nowadays that for people to completely ignore it seems ridiculous. Which is why I really love Obvious Child. The film not only faces the subject head on, but it handles it amazingly well without sacrificing a sense of humor or drama or romance. It’s not a huge, life-changing event for Donna, played by Jenny Slate, it’s simply another bump in the road, a hiccup that creates another problem. And perhaps that’s the best and only way to approach this kind of subject. This isn’t about what abortion means as a whole, but about what it means to the individual. And for Donna, she’s simply not ready. She’s figuring her life out, trying to be who she wants to be, and she fully acknowledges that she couldn’t give a baby the kind of care it needs and deserves. It’s very mature and Slate plays the part beautifully, really capturing the vulnerability of a person in that kind of situation. Written and directed by Gillian Robespierre, the film is 100% from a female perspective, and that may be the most important aspect of Obvious Child. It’s not hindered by judgment or filtered through any sort pre-digested idea of what is “right” or “wrong.” Instead, the film simply examines what it means to a young woman who is still trying to get her life together. And maybe not enough people take that into consideration.

Wages of Fear (1953)

Following a group of four men as they must drive two trucks loaded with highly unstable nitroglycerine over mountains and some of the bumpiest dirt roads you’ll ever see, it’s safe to say that Wages of Fear is one of the most tense experiences I had watching a movie all year. What really amazes me about the film is how well it still works, and I mean that in terms of all aspects of the film. Fear is fear and dread is dread no matter how you slice it, but there is a sub textual narrative going on in the film about lower class citizens getting the worst, most dangerous jobs that still feels entirely relevant to our modern society. The characters are not taking on this deadly task because they are brave, but because they need the work and it pays well. They are taking what is given to them, even if that means putting their own lives on the line, and that is what makes the film’s extended sequences of suspense particularly impactful.

Martin (1978)

I’m a little torn about Martin, to be honest. Coming out just before the ubiquitous Dawn of the Dead, Martin is director George A. Romero’s contemporary take on vampires and it’s honestly a bit of a hodgepodge. It is creative in the way it is never clear whether the titular Martin really is a vampire or not, I’ll give it that, but it is also very, very much a 70s film in some of the worst ways. That means it meanders a bit, it’s highly obsessed with sex, and it is more than a little out there. But at the same time, the film slowly builds to such a grisly, surprising, inevitable outcome that I couldn’t help but gasp and cheer at the insanity of what I was watching. It’s a trip and while I don’t know if I would recommend it to everyone, for the Romero and horror fans out there, you’ll find something to like.

John Wick (2014)

Sometimes you just need to see some Keanu Reeves. Sometimes you just need to see people mercilessly shot in the face. And once in a blue moon, you get both in one glorious package. John Wick isn’t a great movie. In fact, its story is almost non-existent. The titular John Wick played by Reeves is an ex-assassin whose wife dies and when some thugs break into his home and kill the puppy his very recently dead wife left him (I am not even joking), he goes on a rampage and hunts them down. It’s basically an excuse to shoot some guys in the face and in various other appendages, but sometimes that’s all you really ask. The action is always at least cool, with some sequences verging into greatness, and Reeves is perfect as the cold assassin with nothing left to lose. It’s unabashedly fun in how gleefully violent it gets and smartly never aims for more than it should. This is pure junk food action cinema.

Big Hero 6 (2014)

I bawled. I’ll admit it. I don’t even care. Big Hero 6 hit me on such a level that I couldn’t stop it because below the surface, this film is about so much more than being heroes or stopping villains. This is a film about grief, about coping with the death of a loved one, and how the way you react will ultimately define the person you become. It’s heavy, especially for a family film, and in the film’s penultimate moments between Hiro and Baymax, one line hit me like a ton of bricks. Of course, this being Disney, the reality never bogs the film down. The film is a pure delight and they may have just created one of their best characters in years in Baymax. The world is colorful, the characters vibrant, and I think it’s safe to assume that this will become a solid go-to film for me in the future.

MST3K

Mystery Science Theater 3000 isn’t actually new to me. I have been watching the show since I was a kid, but lately I’ve been catching up on a whole list of episodes I never saw and it surprised me after not having seen it in years how easy it is to fall back into the groove of it. The people in these shows are like long lost friends, and even when the episodes are not as great, I find that I just like spending time with this guy and his robot friends as they watch terrible movies and do nothing but crack jokes. MST3K is one of the fuzziest, warmest blankets I can think of and whenever I have a rough day at work, I find that putting on an episode of this always lightens my mood.

Willow Creek (2013)

If you thought or were hoping that found-footage was dead, you really need to see Willow Creek. I’m hesitant to talk too much about the film because part of what made it work so well for me was that I didn’t know what to expect. All I knew was that the film follows a couple as they go through the woods to try to find Bigfoot. The rest was a surprise and while I won’t go into details, I love how much of a slow burn the film is. It takes its time, lulling the audience into a false sense of security, and when it finally starts to play into the horror, it hits hard. Again, I won’t go into details, but it perfectly captures why I refuse to go camping. It’s terrifying.

The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 1 (2014)

I think what makes this series so special is how it builds on the books, how it twists the material ever so slightly so the focus is actually on the revolution than the bland love triangle between Katniss, Gale, and Peeta. Where the books gradually lost my interest, the movies have continually made me a bigger and bigger fan. As a follow up to last year’s Catching Fire, Mockingjay – Part 1 is incredibly dark. The world of the film is in all out revolution, which means many, many people die and director Francis Lawrence smartly never looks away. It would have been easy to sugarcoat the actual reality of a revolution for a YA audience, so by showing the revolt for what it actually is, it adds a nice heft to the film. Of course, by cutting the book in half, the story feels unfinished, but this is a rare case where making it into two movies actually makes sense to me. Overthrowing a government and the society it has created is no small feat and expanding the story actually makes it seem like it matters. Now it’s just a question of whether the filmmakers can stick the landing.

Sister Act (1992)

Yeah. Sister Act. I don’t know if I would ever call Sister Act a great movie. It’s fine. The humor is a little broad and the tone fluctuates a little too aggressively, but Whoopi Goldberg is entertaining enough in the lead role, Maggie Smith does what she’s supposed to do, and Harvey Keitel seems to be having fun as the cartoon version of a mobster. It is what it is. But sometimes it’s not so much about the movies themselves as it is what the movies represent and the memories they bring to mind. Movies are an experience and sometimes the best experiences they can create are the ones we share with others, even if that means one person has seen the film a hundred times and the other is seeing it for their first. They are not just ways to experience stories, but ways to connect and to foster relationships. I don’t know if I will ever necessarily love Sister Act, but it will always mean something to me now and bring to mind memories of a time, place, and a specific person. And for my money, that is one of the strongest reactions anyone can have to a film.

“Ninety percent honesty.”

I struggled with Christopher Nolan’s newest film, Interstellar, the first time I saw it. It’s far different from what the trailers led me to believe, which, in theory, is great. There’s nothing quite like that moment when a film legitimately surprises you, when it veers left when you expect it to turn right. It can be jarring, but it can also have an immense impact, reshaping the story and the experience into something entirely new. But the stark contrast between expectation and reality in terms of Interstellar threw me off balance. The first half of the film is lovely and clever and full of so much love of and reverence for science that I couldn’t help but fall for it quickly and completely. Instead of celebrating power and physical strength, it is an ode to knowledge and to expanding our minds in the face of immense odds, not only to better ourselves as individuals, but to better humanity as a whole. It’s a wonderful, important sentiment for our age and I do nothing but applaud Nolan’s insistence in the film that knowledge is key. But then there comes a moment about halfway through the film where the main characters, after narrowly escaping death, have a conversation about what they should do and where they should go. It’s one of many conversations riddled with scientific jargon and theories, but it becomes painfully clear after one single contradictory line from a character what story is really being told.

I hoped beyond hope that the story would be more than what I feared, that it wouldn’t go that route. But as it continued, my hopes and expectations deflated. It wasn’t just what I feared; it was worse. Setups were dashed, ideas were wasted, and what started out as incredibly ambitious gradually soured into something more mundane, albeit with the added flair of scientific theory as a backdrop.

But I can’t leave well enough alone.

“Ninety percent honesty.”

I saw the film again, this time with the knowledge of what the film is “actually” trying to accomplish rather than what I wanted it to be. With my expectations altered, I figured I’d maybe be able to enjoy the film more; after all, if it doesn’t work on one level, maybe it works on another. And sure enough, I was quickly able to tap into the slightly shifted wavelength of the film with ease. The film’s first half is still lovely with some great ideas and imagery, and with the new expectations, pieces fit better than before. Subtle (and not-so-subtle) setups were clearer, themes became highlighted, and it felt like more of a whole.

And then came that definite, discernable moment yet again. And once again, I couldn’t help but cringe. It’s grossly out of place, it’s boring, and it’s unbelievably on the nose. Had the Nolans kept the sentiment hidden in the background, a la Inception, it wouldn’t feel so out of place. But by making it the ultimate point of the film, it stops the film’s factual, scientific approach to space dead in its tracks. The film barrels on and Nolan smartly throws some tension and action onto the screen to distract the audience, making science seem like the idea of most import, but the film inevitably rounds back to the mundane in its final 20-30 minutes. And for a film that leans so heavily on fact and knowledge to then fall face first into open, basic sentiment, it’s easy to see why it feels so off.

For the good majority of its runtime, Interstellar is rooted in hard science fiction. It may deal with some very high concepts, but it is almost all based on real-life facts and theories. From worm holes and black holes, to relativity and the idea of time as a higher dimension humans can only perceive in a single, straight line, the film feels almost slavishly devoted to being honest. So much so, in fact, that because so many theories are thrown at the audience in such a relatively short amount of time, some of them are hardly even explained. It is a near constant onslaught of exposition, of explaining why time is relative or how black holes work, and by the end of the film, I could easily see people not only feeling like they were entertained, but feeling like they learned something. It is, in a weird way, a Cliffs Notes Hollywood explanation of astrophysics, a crash course in universal mechanics. So why render the immensely scientific impact of the film moot in its final twenty minutes?

“Ninety percent honesty.”

That’s a bit of a running gag in the film. A robotic crew member (yes, there are robots) is asked what his honesty meter is set to; he replies, “Ninety percent.” When asked why just ninety, his response is that anything higher may not be the best thing for emotional creatures such as humans. Giggle, chuckle, laugh; it’s meant as a joke and it plays as one. But to me, it defines what Christopher Nolan and his brother Jonathan have done with Interstellar: they’ve watered it down just enough so people will walk out feeling good about themselves. I’m not saying the film needs to be dour; if anything, I love how hopeful and optimistic the story plays at times. But sentiment is easier to digest than fact; feeling and emotion is easier to connect to than cold, hard knowledge; and that is reflected in the film’s final twenty minutes when fact and theory is cast aside for something a little broader, something a little easier to understand. And none of it is earned. Sentiment is injected into the film’s marrow only when it’s necessary, resulting in characters making huge leaps in logic and reacting as the script dictates rather than as real people. It’s amazingly wrongheaded, especially considering how much faith is put in the audience for the rest of the film’s runtime. Make no mistake, the film goes big, weird, and surprisingly complex in terms of the theories it plays with, and Nolan trusts the audience to keep up. It’s a film you have to really pay attention to in order to follow along and I admire that. But when it’s abandoned for the easy sell, I find it hard to fully forgive.

Look, Interstellar isn’t bad, don’t get me wrong. There is enough about it I love that I would recommend it to everyone to check it out on as big and as loud a screen as possible. The film is so clearly inspired by 2001: A Space Odyssey that I almost feel like Stanley Kubrick should be credited somewhere (the Monolith from 2001 is even featured prominently in the film). Hans Zimmer’s score is majestic, the visuals are so grandiose as to almost be overwhelming, and it so based in science that I can’t help but love some of it. This is a film where space is silent, enormous, and terrifying and Nolan captures it all beautifully. But to have the story suddenly jump from fact to nonsense on a whim is not only confusing, but disappointing. Ninety percent honesty may be enough for some, but for me it doesn’t quite cut it.

Maybe a cool ninety-five percent would have done the trick.

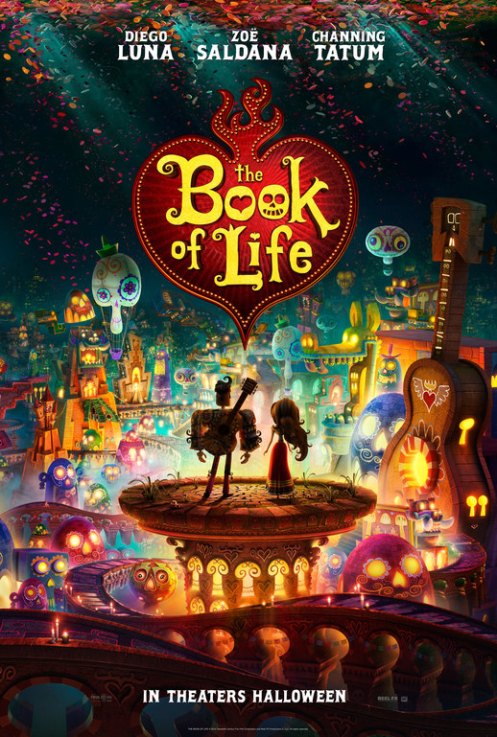

A museum tour guide leads a small group of rambunctious kids through a darkened corridor. Broken and cracked pottery lines the walls, cobwebs have grown over every corner, and the kids chatter with each other, apprehensive and skeptical. Where are they being taken? What are they going to see? It’s a part of the museum none of them have ever witnessed before and it by no means looks like any place a child should be. The tour guide leads the kids into a darkened room. A second passes and the guide breaks the silence.

“Behold the glorious beauty of Mexico!”

The lights flash into life and the kids are surrounded by very old, very traditional Mexican art and architecture. Bright, vibrant colors fill the room; intricate shapes and designs adorn every wall and pedestal; and, yes, there are depictions of skulls and death, but in a way that the dead are being honored and celebrated rather than feared and mourned. The children are overcome with awe.

And so am I. This scene occurs within the first few minutes of The Book of Life, and in that short amount of time it manages to be more culturally aware than any mainstream release I’ve seen in years. It’s astounding and gorgeous and 100% willing to acknowledge that, yes, there are cultures and peoples other than WASPs and they too have their values. And as a proud person of Mexican descent, that means so much. I try not to bang on the race drum as much as possible and for the most part, I don’t view movies or TV or any kind of media through that lens. A good story is a good story, regardless of the skin color of the actors. But it calls attention to itself now and again and this, for me, is one of those moments.

The second that light flipped on in the museum and those Mexican artifacts are placed front and center, a chill literally ran down my spine. This type of loving representation of another culture is so rarely seen that it not only highlights what makes The Book of Life special, but it places a large spotlight on just how little other cultures are represented in the mainstream media. This is a film that is so steeped in Mexican culture and customs and heritage that it’s hard to fathom it even exists in a mainstream format. The work director Jorge Gutierrez has put into making the film as authentic as possible is on full display, seemingly filling the screen with as many traditional Mexican points of reference as possible, but what makes it so wonderful is that it never feels forced, like he’s going for the easiest references that anyone will get. That’s not to say that people will not understand the film unless they are Mexican, but instead of nudging the audience as if to say, “Heh, get it? Because they’re Mexican,” everything simply is. It’s never explained why the characters are made to look like wooden puppets; they just are because it’s part of the culture. It’s a wonderful, beautiful, subtle way of representing a place and a people without going out of their way to draw attention to it. Rather than explaining it, Gutierrez allows the audience to simply experience it.

And yet, as much as the culture drives the film, one of the best things about The Book of Life is that the culture ultimately doesn’t matter. Mexico is the backdrop and the dressing for a very traditional story (no matter your heritage) of fighting for love. It is, at its very core, a classic Romeo and Juliet tale with the added flare of Día de los Muertos to add some vibrancy and an additional narrative thread about family and one’s place in their family tree. It’s familiar, but it’s told well and it goes to show that universality has nothing to do with heritage or culture or one’s role in society, but with emotion, plain and simple. The imagery used in The Book of Life is stunning and expressionistic and weird and while it means a lot to me, it may very well mean nothing to a good many people. But that one fact doesn’t mean the story can’t work for everyone.

Here’s the thing: The Book of Life isn’t a great film. It’s a little broad, it’s a little slow, and it has an over-reliance on pop music. But even those minor pitfalls have caveats. The humor may be somewhat broad, but it’s tinged with a tongue-in-cheek attitude and it allows the filmmakers to include some very specific, very offbeat jokes that made me cackle. The film may meander a bit at times, but I wouldn’t begrudge the filmmakers for it, especially since it allows the audience to really soak in all of the beautiful imagery. And the pop music may be a bit ever present, but when all of them are given Mexican twists, including a norteño version of the hit Mumford and Sons song, “I Will Wait,” complete with accordion (a version you have to hear to understand and that I vastly prefer to the original, by the way), I find it hard to really complain about them. It has some minor issues, but what Jorge Gutierrez along with producer Guillermo del Toro (the one and only) have put out is a declaration that not everything needs to be whitewashed in order to work or sell.

I’ll put it another way; three seats down from me was a middle-aged woman with her little girl. The girl was maybe three or four years old at most with blonde hair and blue eyes; she was about as apple pie as anyone could be. But by the end of the film she was clapping and cheering for the main characters and dancing in the aisle to the film’s abundant use of mariachi music. That is something I can honestly say I have never seen before and I certainly hope it’s not the last. Culture is not a barrier; it’s a window, a lens, a point of view. And film allows audiences to witness and be a part of that point of view, if only for a couple hours.

Sometimes you don’t really know what it is you’ve been missing until it’s suddenly there, a part of your life. The Book of Life may not be great, but it represents exactly what I wish Hollywood would be unafraid to do; it embraces culture and celebrates it. I never really realized how much I was missing or craving that, especially in terms of Mexican iconography, until I saw this film. It’s respectful, it’s caring, it’s loving, and, best of all, it’s inviting. And I will always celebrate The Book of Life for that.

It has been a bit of a rough few months. In one hand is the current movie landscape, which has been far less than stellar, offering few films worth seeing, much less worth talking or writing about. And in the other hand, I’ve been going through a big transitional period in my life the past few months. I’ve moved from my home of the last 20 years of my life to a city 1000 miles away that is altogether unfamiliar to me and where I know no one, so to say my mind has been a bit scattered is an understatement. My time has been spent elsewhere, my mind more focused on other (arguably more important) things than watching movies or shouting into the void in order to voice my opinion on them. To be perfectly honest, I just haven’t felt up to writing. Instead, while taking some downtime to try to figure out the nonsense I call my life, I’ve been catching up on old TV shows I never watched. Shows like Fringe, Flight of the Conchords, and The Sopranos have always been on my “To Watch” list, so what better time to devote weeks to watching a single show than during what I consider to be a filmic drought?

The thing is, I started watching these shows in the hopes of maybe writing about them once I got through them. The Sopranos is critically acclaimed, Fringe and Twin Peaks have enormous cult followings, and Flight of the Conchords just sounded so strange to me that I figured writing about it would be a necessity. But in each case, I was left simply wanting a bit more. I made it a season and a half into The Sopranos before admitting I was bored and allowing myself to quit. Fringe is wildly ambitious, but its serialized nature left me interested only half the time (and thus I stopped about halfway through). Three episodes into Twin Peaks and I knew it just wasn’t for me (which is the same way I’ve felt about almost all of David Lynch’s projects). The only show I finished and enjoyed more than I anticipated was Flight of the Conchords, but even that was so hit and miss with its dry humor and conceptual gags and songs that I can only say I’m mostly a fan of the show. Nothing grabbed me. Nothing made me anticipate watching the next episode. When all I wanted was a show that would transport me and maybe help pull me out of the seemingly endless funk I’ve been in, nothing pushed me to write.

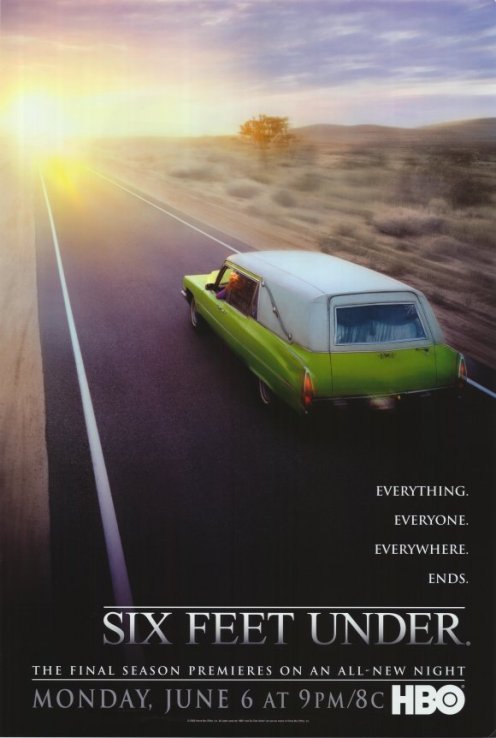

When I started the first episode of Six Feet Under, however, I was almost immediately hooked. Following a family who lives in and runs a funeral home as they deal with death on a practically daily basis is an intriguing concept on its own. How does that affect them? How do they learn to handle death, both on the macro and micro level? What does death even mean, if anything, to the people who must rely on it for a living wage? But Six Feet Under couples this sort of examination with some very dark, often time gallows humor, and the effect is fantastic. It allows the show to be poignant without edging over into sappy, sad without being maudlin. If anything, the show is downright quirky at times. The characters are prone to vivid daydreams wherein they say or enact their true feelings (which means characters break out into song on more than one occasion), or else they see and speak to visions of the people they are embalming and sewing and stuffing. It’s a crafty, clever way to visualize internal monologue and any given character’s deeper, sometimes subconscious fears and it lends the show a life and vibrancy that I would never have expected coming from a show ostensibly about death.

But with all of that said, Six Feet Under is not a perfect show. It has a tendency to have characters repeat storylines, the humor doesn’t always work, and there are a few characters (series regulars, mind you) that I just never came to like. Hell, there are aspects of the show that, in my eyes, border on racism/xenophobia so much that I was actively angry about what I was watching (an argument for another time). And yet, despite these problems, I found myself continually coming back to it. Issues that may have driven me away from other shows didn’t bother me as much in the context of Six Feet Under, and for the majority of the show, I just couldn’t place why. I was drawn to it in a way I did not understand. I knew I really liked the writing, the performances, and (most of) the characters. I knew I was relating to the character of Claire, a young artist struggling to be true to her creative self, on a strangely personal level. Basically, I knew I liked the show, but I had enough problems with it that I sometimes wondered why I kept returning for another episode.

In the show’s final season, it finally occurred to me what was happening. On the surface, Six Feet Under is about living life in the constant face of death, something that is not just true of funeral directors, but of everyone. We are all headed for the same place, that same final outcome that nobody can outrun, and all we can do is live in the moment and try not to be overwhelmed by the awareness that this is all just a fleeting glimpse. It is a dominant theme in the show and the writers take their time pontificating about it and examining how people deal with that simple fact in different ways. But it’s all just dressing, the most noticeable (perhaps most flavorful) part of the meal. The real nutrition comes from what is beneath it and it is in the show’s last five episodes that it became painfully clear to me what the show is really about: family. Not just the family we are born into, but the family we make for ourselves, the people we choose to surround ourselves with. It is a subtle component of the show, one I think a lot of people could easily overlook as simply being a common dynamic of drama (after all, what is family if not drama), but it’s potent. The show’s first episode opens with the death of one of the family members, tearing the family apart and spiraling them in different directions as they struggle to fill in the gaps. They argue and bicker and are constantly at each other’s throats, so each of them looks for comfort and love elsewhere, in other people. But no matter how far they go, how much they distance themselves, they are there for each other. Not because they have to, but because they love each other. That is family. Family is not blood. Family is love. Family is understanding. Family is going hand in hand through life into the face of death. And all of this culminates in the show’s breathtaking final moments, wherein the inevitable outcome of each character is shown with family by their side, juxtaposed against a character just beginning her new life. Life may be finite, but family is forever.

So is it really any wonder why I loved Six Feet Under despite its faults or why the show worked on me on such a subconscious level? Here I am, 1000 miles away from my family and loved ones, watching a show that is ultimately about the strength of family and what it means to be a family. Through good times and bad, they are there, loving and supporting and caring. We may be separate, but we are all going through this life together, hand in hand.

And at this point in my life, that’s really all I need or want to know.

The original Japanese Godzilla from 1954 is one of the great metaphors in cinema history. Released only a handful of years after the nuclear bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the film is a painfully clear depiction of a country struggling with the aftermath of war and coming to terms with what it means to have that much radiation and destruction heaped onto a city. Some people may scoff at the dated effects, but that original film is, for all intents and purposes, a horror movie, a film where humanity is forced to face a monster of our own arrogant design. It is a masterpiece, a snapshot of a country at a very specific moment in time. It is, to me, the quintessential Godzilla.

That said, I am fully aware that Godzilla as a character has evolved since that original film. Since then, the character has been approached, it seems to me, from one of two ways: either Godzilla as metaphor, a la the original version, or Godzilla as blockbuster, wherein the creature is really nothing more than a giant monster that fights other giant monsters and destroys everything in its path. It may seem odd, but that’s actually part of what has made the Godzilla series so fun and lasting. No other film may match the raw power of Ishiro Honda’s original creation, managing to wrestle an entire nation’s fears and anxieties onto the screen, but it is hard to deny the simple pleasures of watching two people in monster outfits throw each other around a miniature city.

So the idea of giving the titular monster a real update with the full Hollywood treatment and a promising young director at the helm seemed unbelievably great. In a time where the entire world is starting to see the ramifications of global climate change, bringing the King of Monsters back into the popular consciousness makes perfect sense. An old metaphor for a new age, right? And coupled with some big budget Hollywood action, it’s bound to be awesome. Right?

Yes and no.

Gareth Edwards was an inspired choice to helm the newest iteration in the long running franchise. His first (and only other) film that he wrote and directed, Monsters, handles the idea of giant monsters running rampant in our modern world beautifully. Relegated mostly to the background and off screen, the monsters of his film work more as metaphor while the film more centrally focuses on character and a very human story. It’s an interesting, creative way to make a monster film on a very limited budget and it only seems like a perfectly natural step to take what makes that film work so well and pump it up to a much grander scale for Godzilla. After all, the original 1954 film is as much about people as it is Godzilla smashing things. Unfortunately, I don’t quite think the idea comes across as well here as it does in Monsters and a lot of that must fall on the screenplay by Max Borenstein.

The film ultimately follows Ford Brody as he and the US Navy track and attempt to destroy Godzilla and his giant monster adversaries, the MUTOs, and Ford’s story is simply a bore. He’s entirely uninteresting, a bland hero who may as well be called Man Tough Guy, given how thinly he is drawn. He and the rest of Navy are the ones who follow the path of these gargantuan creatures, witnessing the destruction they leave in their wake rather than having any sort of hand in the outcome, and I found myself just not caring about them. Or any human character, for that matter. The only one who really registers is Ford’s father, Joe, played by Bryan Cranston. He is given the best non-monster scenes in the film, giving his character a sad powerlessness that is perfect for the tone of the film, but he is disposed of much earlier than the ads may lead one to believe, leaving the film with a cast of flat characters who practically Forrest Gump their way through the film, simply showing up at the wrong place at the wrong time for the majority of the giant monster battles and it grows tiresome very quickly. And given the talent involved, it is simply frustrating. I may not be a huge fan of Aaron Taylor-Johnson, but he is better than this, Ken Watanabe and Sally Hawkins are almost completely wasted, and Elizabeth Olsen, arguably one of the strongest young actors working today, is given almost nothing to do but worry and cry a lot.

But there is a silver lining to the film’s focus on characters, however flat they may be. If there is one thing the film gets exceedingly right, it is the sense of scope and scale, and the way Edwards utilizes the size of humans compared to the enormity of the monsters, several times in a single shot, is, simply put, astonishing. By focusing on the characters so heavily, the effect when he finally shifts focus onto the monsters is amazing. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything quite like some of the shots Edwards has composed for this film. They are beautiful and awe-inspiring and terrifying all at once and they perfectly capture the fear that would be an inherent part of anyone if these creatures were to ever exist in our reality. In other words, it looks the way Godzilla should in our modern landscape. It’s big, it’s brutal, it’s scary, and Godzilla and the MUTOs never feel out of place. The way Edwards utilizes smoke, fog, and any way to partially obscure the monsters makes them feel entirely natural and part of the world around them. It’s fantastic direction and amazing work from the army of animators involved.

Everything with the monsters is great. From the character design to the sound design, this new Godzilla is the modern approximation of the original Toho creation. It looks and sounds the way the creature should. The MUTOs, on the other hand, may be a little generic, looking a bit too smooth and a bit too much like the Cloverfield monster, but they’re fitting. They look and move similarly to classic Godzilla monsters, fluid, but slightly stilted, so when it’s finally time for some giant monster-wrestling action, it’s hard not to think of classic Godzilla matches. It’s as loving an updated entry in the series could possibly be, easily placing itself within the Godzilla pantheon.

Unfortunately, by the film’s end, I was left with the resounding thought of “That’s it?” Normally, I wouldn’t be one to hold that against a film. If the story the director is telling is one of human struggle as they simply try to survive a giant monster attack, then the film should be viewed on such a level. But Godzilla doesn’t seem quite sure what it wants to be. It sort of wants to be the big blockbuster version of the movie with giant monsters going toe-to-toe, but Edwards keeps so much of it off screen that it feels gun shy. It also sort of wants to be a monster-as-metaphor movie, but almost any sense of metaphor is lost. By kicking around both ideas, neither fully lands and it makes the whole film feel like it works better on paper than in execution.

There are great moments in Gareth Edwards’s Godzilla, don’t get me wrong. It can be scary, it can be intense, and it can sometimes be so crowd-pleasing that it made me want to throw my fist into the air in triumph. But they are fleeting moments in a story that is mostly a slog to sit through. Had there been more giant monster action, I would forgive the poor characters. Had the human story actually been engaging, I would be perfectly happy with the monsters being kept largely in the background (a concept I love, by the way). But without either, by not falling on either side of the fence, I was simply left wanting. Not even one side in particular, just something. Because this is a combination of fantastic elements that should make something truly great, but merely made a film that is mostly alright.

Let’s put it this way. Noah is going to piss off a lot of people, mostly those on the more religious end of the spectrum, which is both understandable and, I believe, completely unfounded. What director/co-writer Darren Aronofsky has done with the story of Noah is audacious and unbelievably bold. Treating the story as interpretable myth rather than sacrosanct scripture, his story of Noah is one of magic and mysticism, of struggle and grief, a story where the word of God perhaps goes a little too far. It is, in a sense, a fairly realistic portrait of what it means to flood the entire world, cleansing it of the sins of man, and the toll it takes on the one man burdened with seeing it through to the end. It’s a harrowing experience… and Aronofsky couples it with the added benefit of huge sci-fi/fantasy creatures and action.

The first half of the film comes across as The Bible by way of Lord of the Rings and as crazy as that sounds, it completely works in the world Aronofsky and co-writer Ari Handel have created and the story they are telling. Noah is essentially the world’s first survivalist. He is given horrible visions of death and destruction from God and quickly realizes it is his duty to build an ark to protect his family and the world’s wildlife from the oncoming flood. But when Tubal-Cain finds out what Noah is doing, he is determined to fight his way onto the ark before the great flood washes everything and everyone away, no matter the cost. The preparation for the flood and the battle are appropriately epic given the apocalyptic circumstances and while the eventual battle itself is fairly quick, it feels decidedly grand in scale. This is a battle where hundreds of people are simply fighting for their right to live and while it never really amounts to a war, the stakes are high enough to keep things tense on both sides of the line.

Of course, the Watchers are where the fantasy comparisons really come into play. The Earth in Noah is not the same Earth we are all familiar with, but a dying world of magic and miracles. Colors are sharper, the scarce plant life is more vivid, even the sky looks subtly different, the distant stars and universes taking permanent residence in our field of view. From the very first frames, it is a world we have never known, so when the Watchers are introduced, gigantic, lumbering fallen angels covered in stone, they seem like a natural extension of the world, one more bit of magic that was simply washed away in the flood. They are astounding creations, intellectually stimulating and visually interesting, the type of characters that would look right at home next to Tolkien’s Ents, but they more importantly highlight one of the things I love about Aronofsky’s approach to this story. The Watchers are not simply fantasy creations, but adaptations of characters from ancient Jewish texts. That may not seem like a big deal, but that kind of mindset, that willingness to pull from other stories and theologies and incorporate all of them in a single story, is astounding and plays across the entirety of the film. The research Aronofsky and Handel did is on full display and it only takes a quick Google search to realize just how much they did. It’s not only technically impressive, but it all incorporates seamlessly to make a story we all know feel new.

The second half of the film is where the story takes a breather and where I hesitate to speak too much about this early on. Set entirely within the ark, this is where Aronofsky and Handel really start to explore the larger context of the event and begin to somewhat question the purpose of it and what it really entailed. This is a vengeful God of fire and brimstone and the destruction left in the wake of the flood is devastating and gruesome. Aronofsky utilizes imagery more akin to a horror movie than something based on a common Bible story and the effect is positively harrowing. It may be a bit too much for some people to stomach, but it serves a larger purpose here.

This is a film that asks heady philosophical questions about faith and God’s will beneath the guise of the story of Noah’s Ark. It’s a complex undertaking and Aronofsky and Handel smartly never give any clear-cut answers. They may lean more in one direction than the other, but they never decry either side. Some will scream sacrilege, others will complain that it even slightly acknowledges the possibility of a higher being, but this nuanced back and forth posed in the film culminates in one of the most beautiful marriages of both points of view that I’ve ever seen that is also the beating heart of the film. Noah is about more than religion versus science or myth versus truth. Hell, even given the film’s big, crazy first half, it’s about more than eye candy and astounding visual effects. This is a story about people, about right versus wrong, about whether or not we deserve to be a part of this world in which we live. Like the best stories, Noah draws some deep, scathing parallels between the world of myth and the reality in front of all of us and it stings. He and Handel pull no punches and by the time the film reaches its conclusion, it’s hard not to feel as beaten down as Noah. It’s incredibly dark, but with the distant glow of hope, and no matter how entrenched it is in religious mythology, Aronofsky’s true intent cuts past all of that to get to something deeper, something more meaningful. I just hope people will be able to get past their own predilections to get to the heart of this beautiful, wonderful, complex story.

My favorite Darren Aronofsky film is The Fountain, another passion project of his from 2006 about the love between a couple that spans centuries. It’s big, a little crazy, and amazingly cosmic, but it is always centered on real human emotions. Noah feels like a natural extension of that. It’s big, a little crazy, and plays with some amazingly heady ideas, but it is always from a very grounded perspective. This isn’t a family friendly telling of Noah’s Ark, nor is it the lampoon against religion I’m sure many people were hoping it would be. It is, instead, something else entirely, a story that looks to transcend and perhaps bring together both extremes to take a good, long look at what really matters. It’s a film densely layered with questions, commentary, and mythological symbolism. It’s a challenging film full of bold, audacious statements. It’s a film to really watch and digest. It’s a film I cannot believe got the funding it did (and I mean that in the best way possible). Noah is challenging cinema of the highest caliber, so it is not only something to praise, it’s something to cherish.

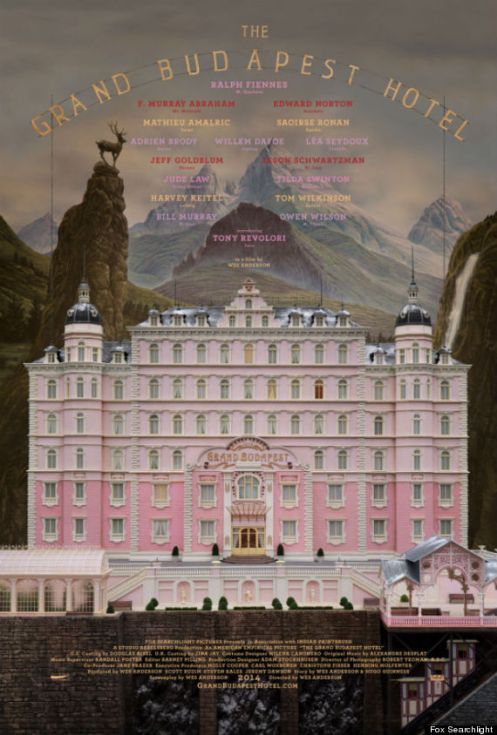

At this point in his career, it seems hard to be surprised by just about any new film by Wes Anderson and that’s not an insult. The man has such a distinct sensibility and point of view that it becomes easy to have an idea of what his films are going to be without ever really having to see a single second of footage. He is a true voice, a director unto himself, the type of filmmaker who warrants his own adjective, and seeing his name attached to anything is enough to warrant, at the very least, an intriguing curiosity.

That said, The Grand Budapest Hotel is probably the first time I’ve been legitimately surprised by a Wes Anderson film. Following the exploits of head concierge of the titular Grand Budapest Hotel, Monsieur Gustave H, and his young protégé, Zero Moustafa, as they navigate their way through the aftermath of the murder of an old, wealthy patron, the story runs a gamut of stylistic genres, ranging from mystery, to romance, to prison escape film and it feels like one of the first times Anderson is really stretching his wings, experimenting to see what he can get away with in these playfully cartoony worlds he creates. There is murder, there is deceit, there is a surprisingly abundant amount of violence and it all adds up to make a film that stands out in Anderson’s filmography as something familiar yet new, and I cannot stress how exciting that is to see.

There is one particular sequence in the film that is ultimately a Wes Anderson approximation of a chase scene through a practically empty museum that feels like something Anderson has never done before. It’s a quick scene and it is as fun and entertaining as his fans have come to expect, but it is suspenseful in a way that is more unexpected than it probably should be. Anderson has more than made clear that he has a wonderful grasp on the craft of filmmaking. His films are all distinctly varied while simultaneously feeling of a piece, so the fact that he can inject a little suspense into Grand Budapest should come as no surprise. But his films also have a definite rhythm, their respective genres never taking prominence over his unique, overarching style, and Grand Budapest bucks that trend in prominent ways. It’s one of Anderson’s first films where it feels like the piece dictates the style, rather than the other way around and the result is a story that, while lovable and unendingly charming, feels dangerous. You’re never quite sure who is safe in The Grand Budapest Hotel and in no way should you be.

But even though Grand Budapest feels like something Anderson has never really attempted before, it is also as comfortingly familiar as you would expect when looking at the trailer. The attention to detail, both in terms of character and world building, is incredible and everything in the film has a terrific handmade quality to it that screams Wes Anderson at the top of its lungs even more so than Fantastic Mr. Fox. Where that film seemed to encapsulate all of Wes Anderson’s signature styles perfectly translated into beautiful stop-motion animation, the heightened nature of his characters feeling more at home than ever before, Grand Budapest feels like the approximate result of what you would get by re-translating those visuals of Fantastic Mr. Fox back into live action. The actors all seem to have a loose, puppet like quality to their movements, as if Anderson had direct control over their most minute of actions, and the effect is delightful. A lot of that may simply be due to how richly detailed and layered the world of the film is, but it’s hard to deny how precise everything is, every choice adding to the piece as a whole.

Indeed, Wes Anderson’s style is as on display here as ever, which will no doubt annoy as many people as it delights, but it’s astounding just how fitting it is to the story he is telling. The film progresses in the form of an unfolding novel, the story broken up into chapters, and for the first time in a long time, it doesn’t feel like Anderson is playing the role of himself, simply doing what he is expected to do, but is instead telling the story the way it needs to be told. It plays the way a mystery novel reads, full of twists, shady motivations, and shocking (and most times hilarious) act/scene breaks, and given the way Anderson typically structures his films in a very similar manner, it gives the whole film a wonderful flow, each style feeding into and playing off of each other. It’s a rather brilliant structure, truth to be told, and as surprised I am at how well it works, it’s so canny, a perfect match that has been hiding in plain sight, that I’m equally surprised it has taken this long for Anderson to attempt something like this.

As per usual throughout Wes Anderson’s filmography, the cast here is impeccable. Ralph Fiennes is wonderfully bombastic as Gustave H, Tony Revolori brings a quiet strength to Zero, and Saoirse Ronan as Agatha is one of the most charming characters in any of Anderson’s films. And, of course, the rest of the cast is filled out with plenty of smaller roles and cameos by actors both familiar and new to Anderson’s growing world of misfits. It always strikes me the performances Anderson gets out of his entire cast, especially the small roles, no character ever feeling like mere window dressing, and the loving way he treats every single person in this film is wonderful. From the smallest characters, like a crippled shoeshine boy, to the strangest, most enjoyable tangents, like the Zig Zag Division or the Society of the Crossed Keys, nothing feels short changed and because of that everyone seems to be completely game to have fun and fill in the world Anderson has created on screen.

Funny, sweet, heartwarming, intriguing, and just the slightest bit bittersweet, The Grand Budapest Hotel feels like the film Wes Anderson has been working towards his whole career. It is both an encapsulation and fantastic reinvention of the already iconic filmmaker and I hope it’s the beginning of a new chapter in his hopefully much longer career. Anderson’s films may be full of lovable, quirky characters, but they have also always dabbled in the darker corners of humanity, his characters consistently confronted with deeper, heavier issues than they may let on. The offbeat humor may be his central focus, but the deep thoughts, the ugly histories, the often times damaged psyches of his characters are the real driving forces of his films. Perhaps it’s a testament to his capability to deftly balance the darker, more real nature of his heightened stories with the light, often times screwy goings on, but The Grand Budapest Hotel simply feels like unexplored territory, like Anderson’s more pessimistic sensibilities are finally coming to the fore. That may be due in large part to the material at hand, but it is nonetheless very exciting to see him try something even this new to him. And if his first foray into the Mystery genre is this good, I can only imagine what he could do with a setup like Clue or any other type of genre. But whether this film ends up being a sign of where things are headed for the filmmaker or simply a flash in the pan, I can’t wait to see where this takes Anderson next.

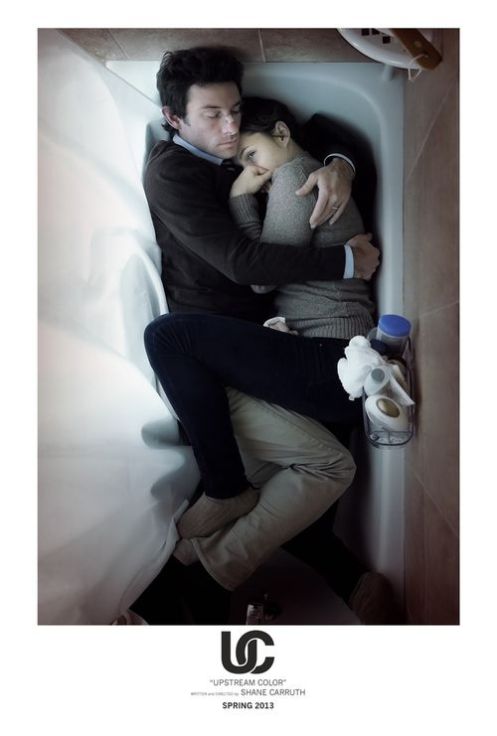

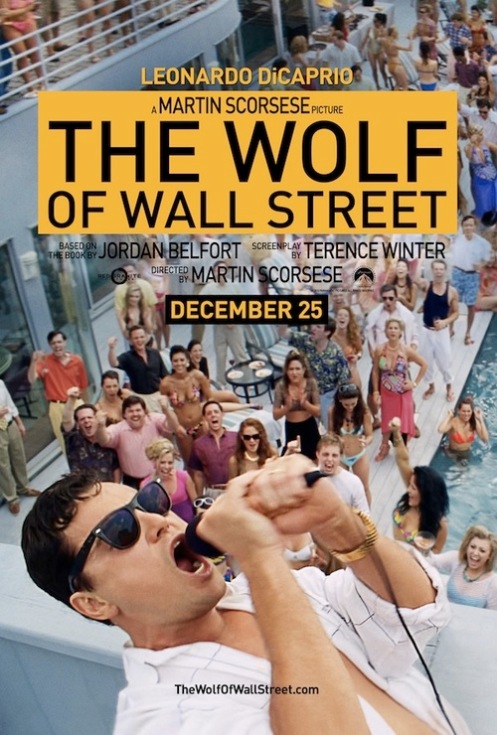

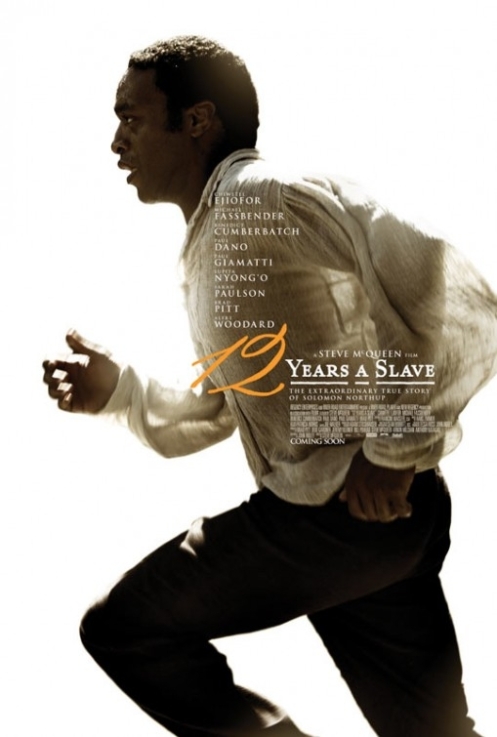

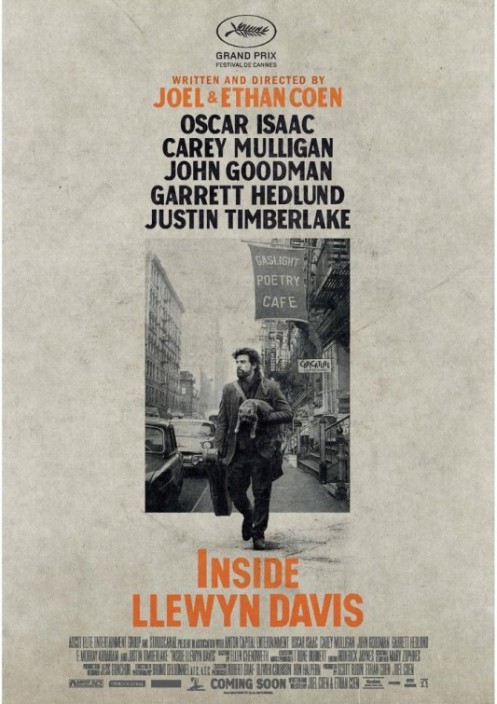

I decided to do things a little bit differently this year for my Top 10. It is basically the same thing as ever, but instead of listing the “best” movies – as I feel like that is not a conversation, but rather a declaration that “you are wrong if you do not like these movies” – I decided to list my ten favorite movies. As such, the order of the list may be surprising, especially the top few. Just keep in mind that this list is a reflection of what was most important to me in my year of movies. There is a definite theme going on with several of these titles and while it was entirely unintentional, I think it’s a strong list that says a lot.

As always, I’m interested to hear from anyone and everyone. So feel free to let me know what you think of my list, how crazy I am for putting what I did at number one, and tell me what your favorite movies of the year have been. 2013 was a very strong year for movies, so it’s hard to make a bad choice.

Let the flaming begin!

10. Pacific Rim

Guillermo del Toro directing giant robots fighting giant monsters! Shake your head all you want, but I couldn’t not include Pacific Rim in my Top 10. After two failed attempts at getting projects off the ground, this is del Toro having fun, making a movie that he wants to see, and the result is an explosion of color and fist-pumping mayhem as humans and monsters battle to the death for the planet. It’s the kind of fun filmmakers hardly get away with making anymore and del Toro and co-writer Travis Beacham smartly ground it in a very human story about loss, trust, and cooperation. It may not be high art, and in no way is it trying to be, but the level of imagination and world building on display is astonishing, full of rich characters and details that make it seem as if the film is barely scratching the surface. I’ll take that over a good majority of the self-serious films released all year any day.

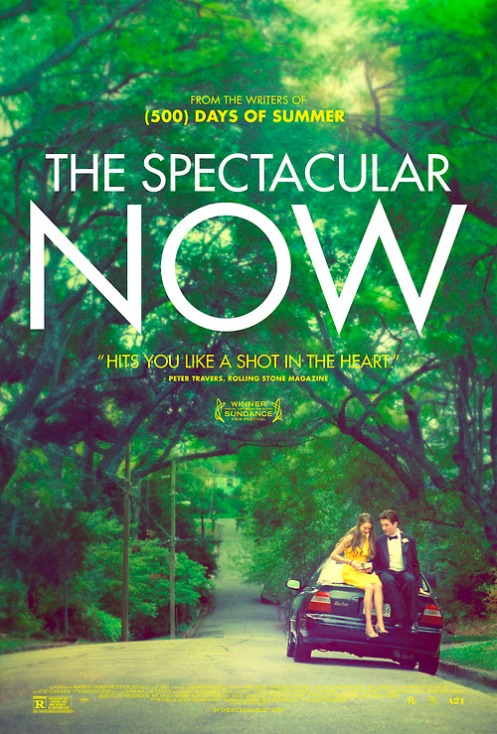

9. The Spectacular Now

This one caught me by surprise very similar to the way last year’s Perks of Being a Wallflower did. Both are akin to John Hughes films for a new generation, very honest stories about life as a teenager, but what makes The Spectacular Now stand out in my mind are the two lead performances by Miles Teller and Shailene Woodley. Woodley is great as the quiet girl next door who is slowly breaking out of her shell and coming into her own and Teller is outstanding as a loud, boisterous, smug guy in school who can smooth talk his way out of (or into) anything. But together they are magic, evoking the kind of warmth and acceptance that is as corrosive as it is fortifying, the kind that only occurs between two diametrically different people. I have some minor issues with the film, mainly in terms of its ending which I don’t exactly think follows what comes before, but director James Ponsoldt captures this sweet, caustic relationship brilliantly.

8. Gravity

Gravity is absolutely terrifying in the way it (mostly) depicts the reality of outer space. The idea of open space has long scared me, but the way it is depicted here is down right monstrous, a vast nothingness that is as dangerous as it is alluring. Many people have remarked that the film, Alfonso Cuaron’s long awaited follow-up to 2006’s Children of Men, is nothing more than the filmic equivalent of a roller coaster, and while that is an accurate description, there is so much more going on. Sandra Bullock as Ryan Stone is fantastic and her arc, while somewhat broad, is wonderful. Despite the film’s bombastic nature, its quiet story gives the film a heart, a reason to care, and the way Cuaron handles both is astonishing. His direction here is confident and assured and it works as an amazing testament not only to his talent, but to the power of all of cinema.

7. About Time